One of the most important findings in the research on Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) in recent years is that people with BPD tend to have a fight-or-flight response that is triggered much more easily than in people without BPD. In this regard, the BPD brain is remarkably similar to the brain of someone with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). Beyond the implication that BPD is possibly linked to some form of trauma, it increases our understanding of BPD in several other ways.

In this article, we’ll delve into the purpose of the fight-or-flight response, why people with BPD have such a sensitive fight-or-flight response, and how this can be improved.

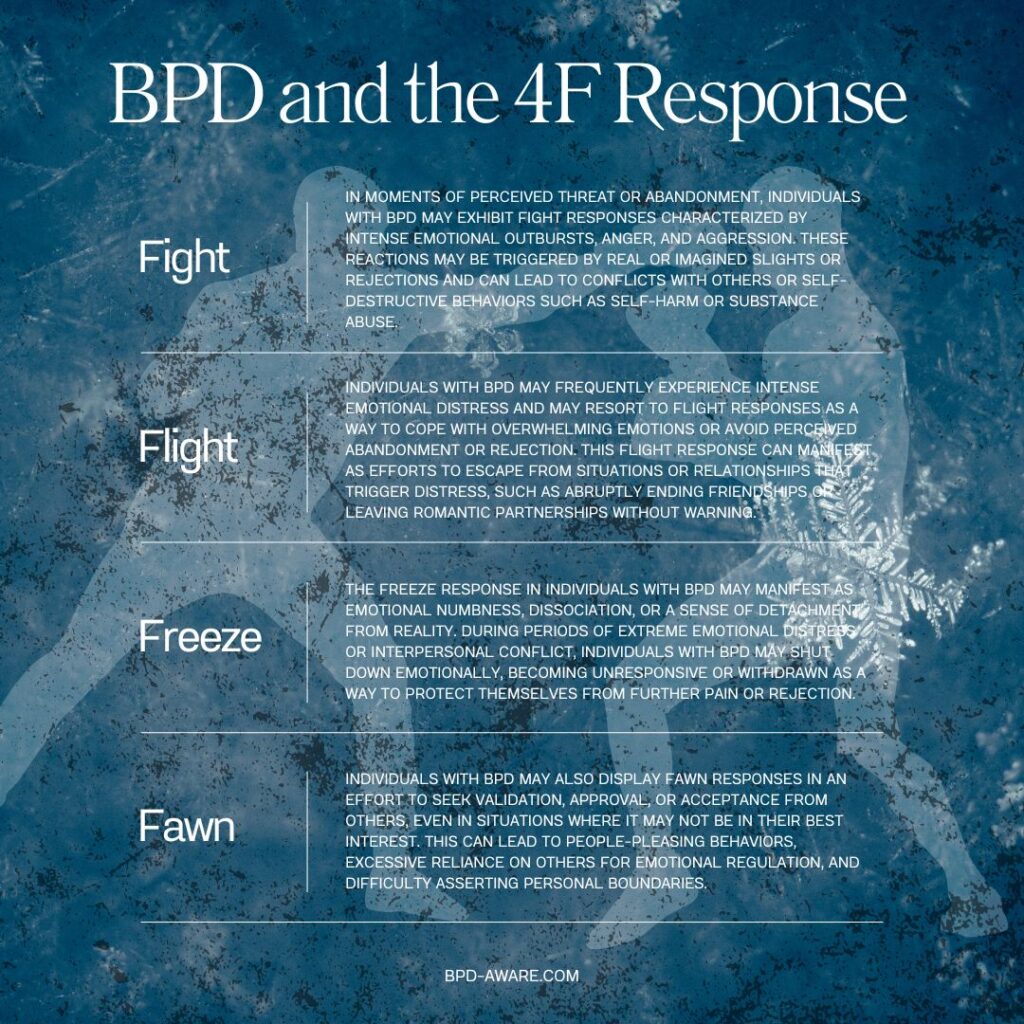

Fight, Flight, Freeze, or Fawn

The fight-or-flight response is a physiological response to any perceived threat or danger. It’s an automatic reaction that is ingrained within us all and intended to boost survival, something that was incredibly useful during mankind’s earliest phases. While it’s less vital now, it still plays a big role in our everyday lives, and an even bigger role if you have BPD.

While many people have heard of the fight-or-flight response, what they may not know is that there are actually two other possible responses to danger: freeze or fawn. Together, fight, flight, freeze, or fawn are known as the 4F response.

In the fight response, someone will be physically or verbally aggressive to ward off the perceived threat. In the flight response, they will be more likely to try and run away from the danger, whether that’s literally or metaphorically. During a freeze response, someone would become immobile and feel frozen – the deer in the headlights response. While in the fawn response, someone would become overly agreeable or helpful and give in to the wants of their aggressor.

People tend to automatically react to danger in the same response most of the time, but not necessarily all of the time. A particularly traumatic event may cause wildly different behavior. For example, someone who’d normally react in the fight response to mild danger might freeze if their life was in very real peril.

The 4F response has three stages. They are:

The Alarm Stage: During the alarm stage your central nervous system is ramped up, getting your body to make a response, either: fight, flight, freeze, or fawn. During this stage, your heart rate will increase and your adrenal glands release cortisol (commonly known as the “stress hormone”) and adrenaline, giving you a surge of energy.

The Resistance Stage: After the initial shock of the event and triggering of the 4F response, your body attempts to normalize and repair itself. You remain on high alert during this stage, in case the danger returns. This stage can last for quite some time and, if you constantly cycle in and out of 4F response situations, your body begins to adapt and learn to live with the higher stress level.

The Exhaustion Stage: This stage is a result of chronic or prolonged stress. As much as your body attempts to adapt, no one can cope with chronic stress for long periods. Eventually, you will wear down and feel depleted, fatigued, and exhausted.

BPD and Fight, Flight, Freeze or Fawn

As we discussed in our previous article (Brain Differences in People With BPD), people with BPD often have significant physiological impairments in how their brains work. This includes physical areas of the brain as well as dysregulated production of several neurotransmitters. More research needs to be done before we know if BPD causes these impairments or if these impairments cause BPD. It’s even possible that both statements are true.

The result of these impairments is that people with BPD tend to be more reactive to stimuli, and perceive danger in situations where other people wouldn’t. Even a normal conversation with a friend can be fraught with danger when you have BPD. The BPD mind races to find patterns of danger in simple pleasantries. “Was that compliment sincere or were they being sarcastic?” “Did they really mean it when they said they’ll talk to me later?” “Are they going to leave now to go and laugh about me with other friends?”

This means someone with BPD enters a 4F response much more often than someone who doesn’t have BPD, and it goes a long way to explaining why many people with BPD react in a way that some would describe as “extreme” to relatively benign situations.

It may also explain why many people with BPD suffer from chronic fatigue, depression, headaches, irritability, and gastrointestinal issues. The BPD brain is constantly on high alert.

With the brain constantly on high alert and so many systems depleted, many of the core features make a lot more sense too. The fear of abandonment, impulsive behavior, mood swings, unstable relationships, and explosive anger all make sense for someone who is mentally on high alert and constantly drained of energy.

Managing the 4F Response in BPD

Now that we know that the trauma response of fight, flight, freeze, or fawn is overactive in those of us with BPD, the question is: how do we cope with this and reduce the impact?

Fortunately, the brain does have the plasticity to change its thought patterns and neurological responses. Reducing the frequency and intensity of the 4F response is possible through a combination of healthy living, smart choices, and proper support.

PLEASE: PLEASE is a DBT skill that involves looking after your physical health by being proactive about health issues as they arise, eating a balanced diet, avoiding mood-altering substances, getting good quality sleep, and exercising regularly. These help to improve all aspects of your health.

Relaxation Techniques and Mindfulness: Learning how to perform relaxation techniques such as progressive muscle relaxation, deep breathing exercises, and yoga helps the mind enter a calm state. Meditation in particular can be beneficial as research shows that mindfulness meditation can aid physical healing of the brain.

Support: Participating in therapy and having good social support around you can help reduce the physiological and psychological reaction to stress. Therapy can also teach you skills that will help you cope with crises and stressful events in a healthier manner.

Learn Your Triggers: Pay attention to yourself and what commonly triggers the 4F response in you. If certain people or events are common triggers then it may be time to find ways to remove them from your life or find new ways to deal with them. Journaling your BPD experiences can be a great way to find what triggers your trauma responses.

Self-Compassion: Don’t judge yourself for your reactions to perceived danger. You didn’t choose your reactions or responses. They are ingrained defense mechanisms. What you can control is how you begin to heal and improve your responses.

Final Thoughts

The relationship between Borderline Personality and the fight, flight, freeze, or fawn response is complex but undeniable. It underscores the nature of psychological distress and trauma responses that are inherent to BPD.

By delving into BPD on a more scientific level we gain a deeper understanding of the underlying mechanisms that drive so many of the core symptoms that people with BPD experience such as emotional dysregulation and impulsive behavior.

We also know that these mechanisms can be reworked and rewired. We don’t have to be slaves to maladapted thought patterns and stress responses. A life with BPD is still a life with hope. With the proper tools, hard work, and discipline, you can change the way your brain and mind works. It’s not easy and it doesn’t happen overnight, but it can be done. You just need to choose to make the change.

Sources, Resources, and Further Reading

- BPD and the Sympathetic Nervous System: https://www.verywellmind.com/what-is-the-sympathetic-nervous-system-425330

- Understanding BPD Stress Response (Fight, Flight, Freeze): https://www.bpd.org.uk/bpd-stress-response/

- The Impact of Chronic Fight or Flight Response on the Development of Borderline Personality Disorder and the Role of Neuroplasticity in Recovery: https://stopbpdstigma.co.uk/the-impact-of-chronic-fight-or-flight-response-on-the-development-of-borderline-personality-disorder-and-the-role-of-neuroplasticity-in-recovery/