Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) has received an increasing amount of research in recent years and some of the most important studies in the field have looked at the physical and neurochemical differences in the brains of people with BPD compared to the brains of people without BPD.

The findings have been startling.

MRI scans and neurotransmitter testing have both found significant differences in the brains of people with BPD compared to those who don’t have BPD. Not only does this give us a deeper understanding of Borderline Personality Disorder, but it also opens the door for new kinds of treatment in the future. It also validates those of us with BPD; BPD is very real and very noticeable under a scientific lens.

Let’s begin in the limbic system of the brain, the emotional control center. As you already likely know, people with BPD often have difficulties regulating their emotions and we’re about to find out why.

The BPD Brain

The Hippocampus

As fun as it might be to imagine the hippocampus as a place where hippopotami go to school, the hippocampus is actually the brain’s data processor. Its main job is to store short-term memories and transfer them to long-term memories. However, it also plays a role in emotional processing, including anxiety and avoidant behaviors. It decides the correct emotional response to a situation.

The problem, for people with BPD, is that their hippocampus is in a constant state of hyperarousal – meaning it constantly perceives situations to be much more extreme than they are, and then sends these messages to the amygdala (more on this later) to be processed. It’s like the messenger game where children sit in a circle and whisper a message to one another until it’s gone all around the circle. The original message becomes twisted beyond all comprehension by the time it gets to the end. This is how the hippocampus and amygdala communicate in people with BPD.

The hippocampus also plays a role in spatial memory and navigation. Some people with BPD report being extremely clumsy and uncoordinated, which could be due to their hyperaroused hippocampus.

The Amygdala

The amygdala plays a huge role in recognizing and responding to emotional stimuli, particularly fear and anger. Even in modern lives, fear and anger can play a vital role in keeping us safe. However, MRI scans show that the amygdala in people with BPD tends to be smaller and more hyperactive than the amygdala of the average person. Also, as mentioned earlier, it often receives unreliable messages from the hippocampus.

This can go a long way to explaining why people with BPD experience emotions much more intensely and take longer to cool down after an explosive emotional episode.

But that’s not all the amygdala does. It’s also involved in emotional learning, social processing, and decision-making. It’s easy to see how a hyperactive amygdala can be at least partially responsible for maladjusted patterns of behavior, difficulties socializing, and poor decision-making – common symptoms in BPD.

The Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis

The hypothalamus, the pituitary, and the adrenal axis (HPA) are all interconnected and interact with each other to function. One of the primary functions of the HPA is the production of cortisol – the neurotransmitter released during times of stress. The purpose of this neurotransmitter is to help during times of stress by converting protein in blood sugar into glucose to boost flagging blood sugar, reduce inflammation, maintain blood pressure, and contribute to the immune system. All good things.

The problem is that people with BPD tend to have hyperactive HPAs which release too much cortisol. This is likely due to the heightened emotional state people with BPD often find themselves in. Too much cortisol elevates blood sugar and can cause heightened blood pressure, fatigue, weight gain, anxiety, and mood swings.

The Prefrontal Cortex

The prefrontal cortex (PFC) is a region at the front of the brain that is crucial for executive functions. These are the functions that enable us to make decisions, solve problems, control impulses, and carry out goal-orientated behavior.

The PFC of people with BPD tends to be less efficient compared to the average brain and sometimes inactive altogether.

This could very well be the reason why so many people with BPD struggle with impulse control, as well as everyday life in general.

A recent study has also found that one area in particular in the PFC doesn’t activate at all in some people with BPD when they experience perceived social rejection. This could explain why some people with BPD tend to cut ties with people very easily or split on them.

The same area (the rostro-medial PFC) is also in charge of attempting to understand other peoples’ behavior. Because it doesn’t activate, this can cause people with BPD to engage in black-or-white thinking rather than taking a more rational, middle path.

BPD Brain Chemistry

Chemical imbalances also play a critical role in Borderline Personality Disorder. We’ve already mentioned how people with BPD tend to experience heightened levels of cortisol but other neurotransmitters can cause issues too.

Serotonin

Serotonin is a neurotransmitter that helps to stabilize moods and behavior. However, serotonin production is often found to be dysregulated in individuals with BPD. This can contribute to mood swings, impulsivity, and rage – all of which are common symptoms of BPD.

Serotonin also contributes to other areas too. It affects appetite by promoting satiety and regulating food intake. Serotonin dysfunction can be a cause of Eating Disorders, something that many people with BPD also suffer from.

People with BPD can struggle with chronic pain. This can be caused by serotonin dysfunction as serotonin influences the perception of pain.

Serotonin plays a significant role in sleep regulation by influencing the body’s sleep-wake cycles. It is the precursor to melatonin, the hormone directly responsible for sleep cycles. Many people with BPD struggle with either getting enough quality sleep or sleeping too much.

Serotonin also influences sexual desire and function. Different serotonin levels can have varying effects on someone’s sex drive. Both too much or too little serotonin can lead to sexual dysfunction such as hypersexuality.

Dopamine

Dopamine is a neurotransmitter that plays a vital role in the brain’s reward system, motivation, pleasure, emotional regulation, and other functions.

Evidence shows that dopamine dysfunction can play a role in BPD.

Dopamine is involved in regulating emotions, so dysregulation can contribute to the emotional instability seen in individuals with BPD.

Another core feature of BPD is impulsivity, something that can be affected by dopamine due to its like to the brain’s reward system. Abnormal dopamine functioning could contribute to impulsive behavior that manifests in ways such as substance abuse, binge eating, and risky sexual practices.

People with BPD often exhibit a heightened sensitivity to stress. Dopamine dysregulation may play a role in increased stress reactivity, affecting both emotional and behavioral responses to stressful situations.

Noradrenaline (norepinephrine)

Noradrenaline (also known as norepinephrine) is a neurotransmitter and hormone that plays an important role in your “fight or flight” responses. It also plays an essential role in the regulation of arousal, attention, cognitive function, and stress response.

It’s believed that alterations in noradrenaline levels could contribute to the heightened sensitivity to stress observed in individuals with BPD. This heightened response can worsen emotional regulation, a core feature of BPD.

Dysregulation in levels of noradrenaline can also influence behaviors related to impulsivity and aggression, potentially leading to overreactions in stressful or challenging situations.

Much like serotonin, noradrenaline also plays a role in pain perception. People with BPD often report high levels of chronic pain, which could be caused by the dysregulation of noradrenaline as well as serotonin.

BPD Brain Health and Treatment Implications

Now we know how the BPD brain differs from the average brain, it’s important to consider what this means for the brain health of people with BPD, as well as potential treatment implications.

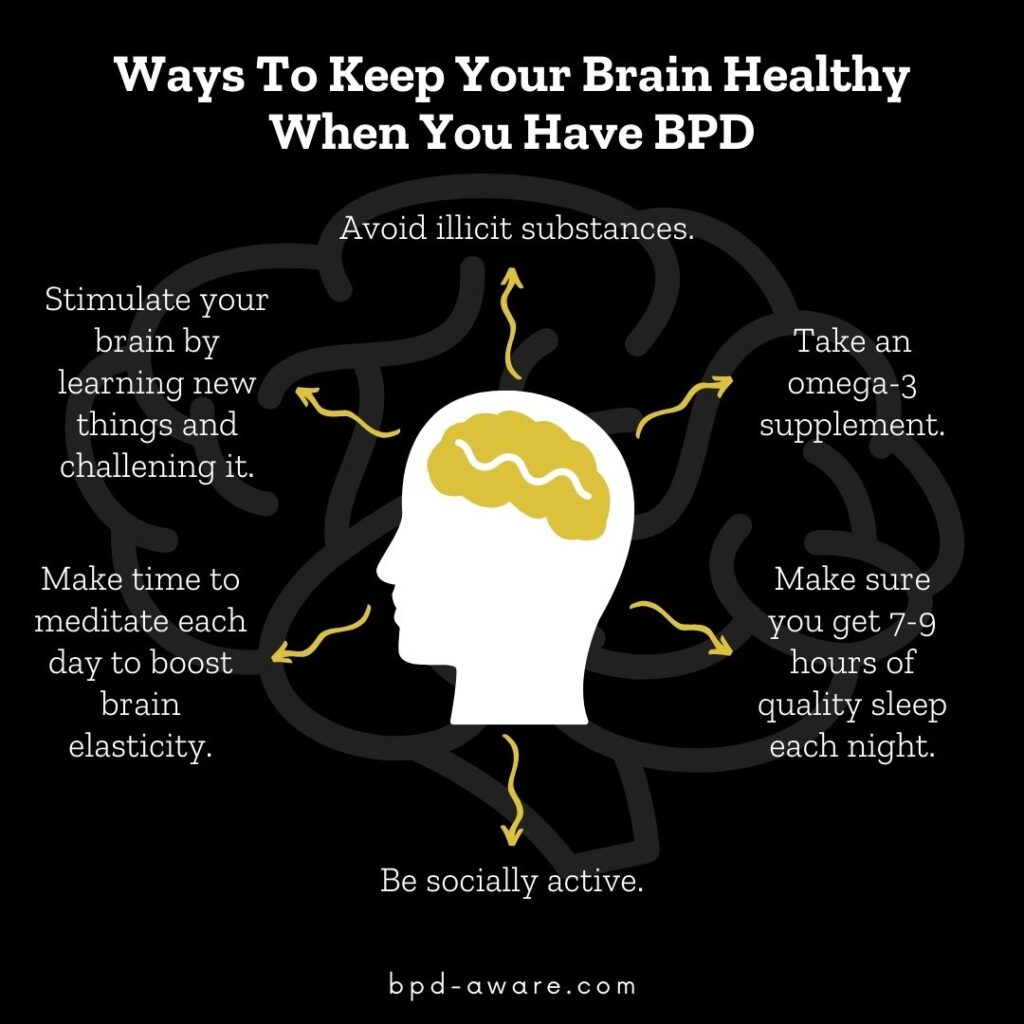

While there may be physical abnormalities in a BPD brain, the brain is capable of repairing itself. Neuroplasticity allows the neurons in the brain to adapt and compensate. Irreversible physical brain damage is very rare and more typically comes from blunt force trauma. By living a healthy lifestyle, avoiding mood-altering substances, practicing mindfulness, and undergoing therapy, your brain can begin to heal and recover.

In the case of dysregulated neurotransmitters, these can be treated via synthetic medication. Most antidepressants are selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) which help to regulate serotonin levels. Many people with BPD take antidepressants already. Dopamine and noradrenaline do exist in synthetic form but aren’t commonly prescribed to people with BPD, although research exists to show that it would be of benefit.

The more we learn about the BPD brain, the more avenues for treatment open up.

Final Thoughts

There is little doubt left that the brains of most people with BPD are different from those without it. What’s still not yet known is whether these physical and chemical differences in the brain are the cause of BPD or a consequence. There’s a possibility that it could be both, like some sort of symbiotic parasite that feeds on its own decay.

But there is hope.

We do know that the brain is capable of healing and repairing itself when it’s treated well. This means a well-balanced diet, quality sleep, exercise, meditation, regular socialization, and therapy. Treat your brain well and it will treat you better in return. Symptoms will diminish and hope can be restored.

In the future, there could be some truly revolutionary treatment options for BPD as our knowledge of the brain and our ability to manipulate it expands. For now, we know enough to know that we need to take better care of our brains than the average person. It’s both an injustice and an opportunity all in one.

Sources, Resources, and Further Reading

- Neuroimaging and genetics of borderline personality disorder: a review: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC1863557/

- The Neurobiology of Borderline Personality Disorder: https://www.psychiatrictimes.com/view/neurobiology-borderline-personality-disorder

- Key Brain Activity Absent in Borderline Personality Disorder: https://neurosciencenews.com/bpd-brain-activity-23541/

- Its All In Your Head: Borderline Personality Disorder and the Brain: https://medium.com/invisible-illness/its-all-in-your-head-borderline-personality-disorder-and-the-brain-c14b66eb0966